In a ‘temporary’ state: A conversation with Shen Li

Shen Li

1985

Chinese architect, furniture designer and photographer

Born in Jiangsu

“I’m more inspired by the act of ‘doing something’. It’s like I’m getting rid of the charm of creative inspiration — transforming it into something more labour intensive, sometimes it’s a spiritual labour, sometimes it’s manual. You start doing something, and the inspiration comes out as you do it.”

Can you start by giving a short introduction of yourself to our readers?

Hi everyone, I’m Shen Li. I was born in Jiangsu, China in 1985 and studied architecture for both my undergraduate and graduate degree. During my graduate studies, I started to take my own photos for fun. After graduation, I worked for an architectural firm in Shanghai, changed position and firm twice, then went freelance. I would do small spatial projects and photography at the same time. After three years of freelancing, I established my own studio, archive, focusing mainly on spatial design and furniture design, but the emphasis is still on spatial projects. Two years into archive, I started a furniture brand called darkdetails. Now our studio does both furniture and spatial design at the same time.

Why did you choose to study architecture in university?

Actually, I didn’t know much about architecture at the time. I originally wanted to study a design-related subject, and because some of my family members’ career was related to the architecture industry, so they suggested architecture as my first choice. At the same time, I also chose graphic design and some other design-focused courses. My initial intention was just to do design, but I didn’t mind exactly which area, because I didn’t know much about it. It just so happened that I got into architectural design and that’s what I ended up studying.

You mentioned that you have been interested in photography since university, was there an opportunity for you to develop it as a career?

I was just taking pictures for fun. I did a lot of photography during my graduate studies. When I was about to finish my degree, I was in Shanghai and probably got some attention from the outside world. Gradually, brands started to contact me asking if I could do their shoots, so I did one. At that time, I didn’t have any experience in shooting commercially, so I was just shooting for fun. But the brands probably thought it was done quite well, so I continued to shoot for them for a few years. I did a few shoots for magazines and other publications in between, but mainly for bigger companies and the brands they represent.

I don’t think of myself as a very professional photographer, but rather an amateur commercial photographer. Whilst doing photography, I was actually also working on spatial projects at the same time and I enjoyed both. But I started to find it difficult to do them simultaneously and felt like I needed to focus my energy specifically on one direction. In the end, I decided to spend more of my time on spatial design.

Being both a photographer and an architect, how do you switch between the two identities when creatively working?

I don’t think it’s a difficult transition for me. Instead, I was curious if some of the ideas from photography could be applied to architecture, or if some of the ideas from architecture could be used in photography.

Maybe it’s not a necessary or mature element for the development of both arts, but it’s new to me, so I’d want to experiment with it.

For you, what are the differences, or similarities, between the two?

The main difference is the technical requirements. Architecture requires a great deal of proficiency in the different subjects of design, it requires very detailed drawings because we do design in millimetres. No matter how big the space is, even if it’s a building of thousands of square metres, the final construction drawings need to be very detailed. It includes water, electricity, heating and other equipment, as well as requirements for floor plans, and so on. Precise details are needed so that when the workers get the drawings they get on with the instructions listed and follow the numbers given directly. Therefore, it is an extremely rigorous and meticulous job. But of course, there is also a very artistic part to architecture.

Technically speaking, photography is perhaps not as demanding. It of course also needs shooting skills, Photoshop retouching skills etc — but compared to architecture, the required level is extremely different from a technical point of view.

They also have so much in common. Speaking on a large scale, the whole design industry, including music, or industries related to culture and creativity, are pretty much the same. As long as you are in this industry, you will find common grounds in others, such as graphic design, packaging design and so on. It’s mainly aesthetic-wise that will have similarities.

To you, what is the most important thing when doing architecture and photography?

When I was doing photography, each stage had another emphasis, because I was concerned with different things at different stages. I still think I probably don’t know much about photography yet. Although I have been shooting for many years, the more I shoot, the less I feel I understand it. In the beginning I was curious about the technical side, I wanted to create a certain kind of texture, including showcasing the technicality of the images. As I shot, I became more curious about experimenting with ideas within the photographs. Then, later on, I became more interested in a certain concept and how I would accomplish that. So, as you can see, each stage varies slightly.

It’s the same with being an architect. I think differently at each stage. At this stage, I am still focused on how to present my ideas more freely in what I make. This is not only limited to architecture, but also to other things I am doing, such as photography. I’m intrigued to know about how I can be more free. I feel constrained or bound by certain things in the process of creating. This can come from previous experiences or from various things. But because I feel restrained, I want to be more free in my creative works.

If you had to describe your own style in a few words how would you describe it?

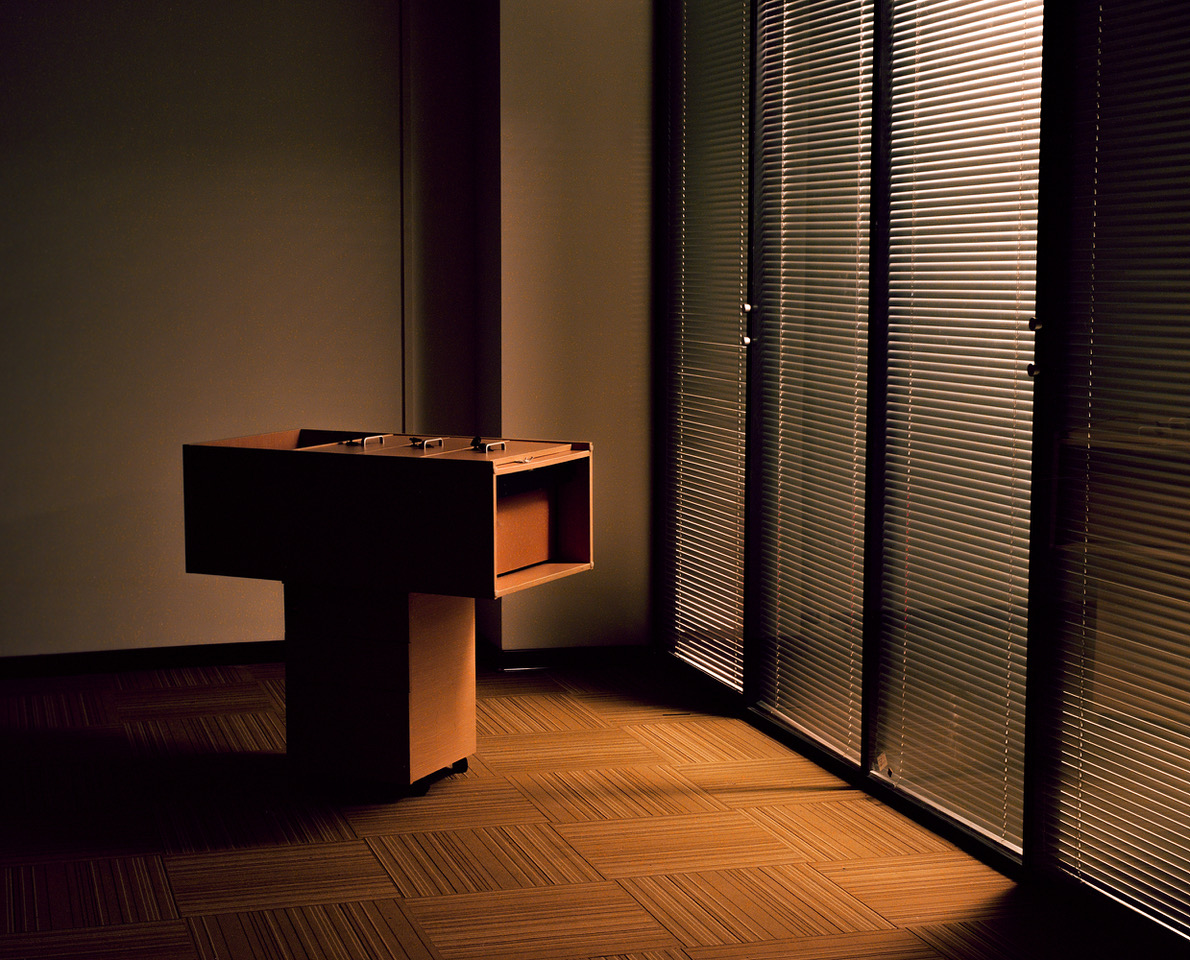

I’ve never summed it up myself. However, one aspect that intrigues me is the state of being ‘temporary’. It’s not solid — it’s temporary, it’s fragile, and it’s also a bit raw and clumsy. But I’m actually quite inaccurate in summing myself up. Because I get confused when I describe myself: is what I’m describing the direction I want to develop into, or have I actually accomplished those keywords through my work? I would always ask myself this question. It’s possible that some parts of what I’ve just summarised are things I’d like to hone in through my work, and some parts of it are things I haven’t done yet.

If you had to name some photographers and architects that’ve influenced you, which ones would you choose?

I’ve been influenced by various people at different stages of my life. There are many photographers and architects that I like, but I don’t have a particular favourite. In terms of architecture, I used to adore the Japanese architectural firm “SANAA” by Kazuyo Sejima a long time ago. Afterwards, French and Belgian studios influenced me more, because I often enjoy their architectural style. Though I actually don’t like that many American studios compared to Europe.

In terms of photography, earlier on, I used to love the Japanese photographer, Rinko Kawauchi. It’s always a different person during a different stage of my life. My favourite photographer in the last few years, and probably one that many Chinese photographers like at the moment, is Torbjørn Rødland, who shoots in a more ironically humorous style.

It feels like you were more influenced by East Asian artists in the early years of your career – has the East Asian cultural context influenced your work much?

Of course — after all, I was born in this part of the world. But the concept of East Asian cultural context is so substantial that I feel it would be difficult for me to describe it clearly. However, I am curious about ‘East vs West’, even if I haven’t deliberately studied it. My dissertation during my graduate studies was on the creative trends of the new generation of Japanese architects. Back then, I would look at research that delved into the information society we live in and what influenced the thinking of this new generation. I guess this is perhaps one of the East Asian influences on my work that you’re talking about.

The other influences are rather more of an everyday experience, including the use of Taobao. I feel that they are phenomenoa that go beyond some of the East Asian context that we get from books. The actual lived experience of using Taobao in China, or sweeping a code for bike-sharing etc., has had a huge impact on those who grew up in this era. It builds a fast-paced life and a set of peripheral experiences that are packaged along this lifestyle.

You mentioned earlier that you were curious about the concept of ‘East vs West’, could you tell us why?

I noticed this when I was writing my graduate dissertation. Japan creates cultural products with a strong national identity, you can instantly recognise that a certain graphic design is Japanese, but at the same time it’s also very contemporary. They can do both at the same time. The new generation of Japanese designers have thrived — including other aspects of their culture too, such as film, music, etc. It’s likely that this saturated industry is due to the fact that Japan’s economic development is a cycle ahead of China’s, but there may be other reasons as well.

Back then, I felt that China didn’t necessarily have a specific aspect of culture that includes both an authentic heritage and contemporary style, whether it’s film, music, culture, architecture or anything else on a pan-cultural level. That’s why I’m curious about the concept of ‘East vs West’. For example, in the future, if we had something that represented both the heritage and contemporary China in a different approach compared to the West, what would it look like? And that would solve the issues of the rapport between the Chinese identity and the contemporary, and will provide the answer to how to integrate between the two.

Why do you think China currently can’t produce works that reflect both contemporary China and traditional culture?

I don’t know about that, and that’s why I’m curious. I feel like I’ve been curious from being a student till now, and over the years I feel like there still hasn’t been a piece of work that encompasses both directions. I feel as if there’s not enough. For example, it’s true that over the years, many fashion designers and the music and film industry too, have worked towards this direction. But I feel like it’s not explicit enough. It’s hard to say what exactly has led to this, I guess it’s intricate. It’s probably a big reason that’s out of the creatives’ hands. Influences from institutions, society and other aspects have all helped form such a situation.

Where do you usually get your inspiration from?

The most direct source of inspiration is reference images. I think everyone in the design industry can’t live without reference images, they’ll always have to go to Pinterest and Instagram. This is one of the most intuitive sources of inspiration that no one can do without. But it’s also about how well you can digest and absorb it, and how well you can translate it. If a design looks like a copy, it means the designer has barely digested the reference image; the designer probably saw it, was directly influenced by it, and then pretty much ‘ate and pooped’, without digesting it. Then the reference image only satisfies the designer’s desire to copy. This is the most intuitive kind of inspiration.

What is less intuitive is the accumulation of all the everyday things: the films you watch, the music you listen to, the strange things you see around the area when you travel, etc. All these things can become inspiration. Often, I don’t actually have a specific inspiration at the start of a project, I’m more inspired by the act of ‘doing something’. It’s like I’m getting rid of the charm of creative inspiration — transforming it into something more labour intensive, sometimes it’s a spiritual labour, sometimes it’s manual. You start doing something, and the inspiration comes out as you do it. It emerges slowly, as if you’re creating a larger field for the thing to be made, letting it collide with each other, and it forms its own order as it collides, as if it organises itself into a piece, and then pulls out.

Do you have a preferred camera?

I don’t have a particular preference. I’ve used both digital and film cameras, especially film: from 35mm, to beginner-friendly film camera kits, to medium format. I haven’t used large format yet. But I prefer film. I guess it’s because I like the texture, which many digital cameras can’t capture. For example, when I take a picture with a medium format film camera, I get a more three-dimensional picture, but with a digital camera it’s hard for me to get that structural feel in a picture. There’s also a different way of taking photos. With digital cameras, people usually take more photos to pick and choose later. But I still prefer the opposite of it — the way film cameras work.

Can you share with us the story behind founding archive?

I started the archive because I thought I needed help with the next project and I couldn’t do it alone. I set up a studio because realistically, I needed to recruit people. Also, I was working from home and felt very slack. Surprisingly, the freelance way of working instead made me feel less free at work. So I felt it was better to have a studio to work and leave every day in order for me to separate my work from my weekend status. I wanted a different lifestyle, that’s why I set up a studio.

Describing freelancing as ‘restrictive’ is interesting. Is it because you feel you need a schedule in your creative work?

It’s because I felt constrained lifestyle-wise. There was a very popular advertising slogan: “Self-discipline gives you freedom”. That’s what I thought at the time. If I did only freelance work, I would be easily ‘kidnapped’ by my own laziness. It’s like you’re supposed to be free, but I feel like I’ve been trapped inside instead.

darkdetails was set up during the pandemic, why did you choose to start a new project at a time when the world was going through such turmoil? What challenges did you encounter while working on it?

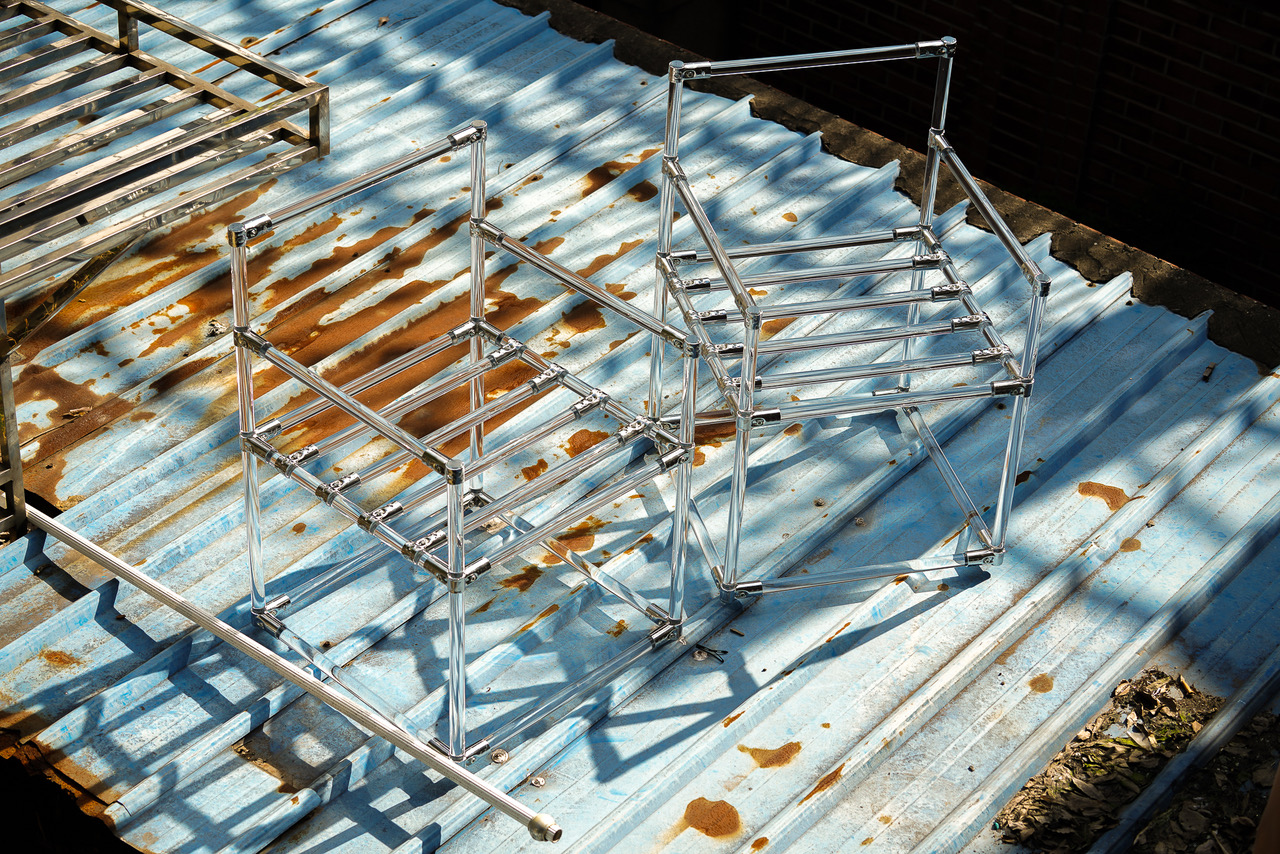

I didn’t really feel the impact of the turmoil at the time; when I set up the studio [archive] in 2019, I felt that I needed some furniture, so I thought I’d make some myself. I hadn’t done much research on furniture, such as what materials to choose, what hardware to use and so on, but I was curious about it. Although I come from an architect’s background, the projects we did when we worked in big architecture firms were often too grand in scale and would lack detail. This is also related to the general context in China for so many years. Design houses and designers in big architectural firms don’t have a sense of grasping the small details. I felt that if I didn’t understand it, I wouldn’t have a fundamental basis to do such a design.

We would do some very big projects at the time, but because it was such a substantial scale, it didn’t make a lot of difference to me whether the corridor space was three metres high or two metres high. Including when you have to draw a table, you give the constructors a drawing and they just do it. But how the table is attached is a detail that many architectural firms don’t have time to think about, because the design cycle in a firm is too short. When you don’t know these details, you often end up doing a similar design to some other firm out there. You spend a similar amount of time, you have a similar depth, you focus on a similar direction, and you’re all inspired by some drawings that you look at quickly before designing each day. So the designs that come out are bound to be similar. I feel that this is no different from a production line.

Instead, I’m curious about the details. For example, how two materials are connected to each other. Once I know how it’s connected, it can be made into furniture, and then it can be turned into a space if I go bigger. I need to understand the hardware from the smallest detail and then slowly and gradually try to turn it into a space or make it bigger. That’s why the names of my furniture are very straightforward. The name I came up with was inspired by the title of a song by Andy Stott, a British electronic musician I quite like: ‘Dark Details‘. The name of the song made me feel that it was in line with the idea of the furniture I wanted to make. So I just used the title of the song as my brand name. I wanted to look at how materials could be connected to each other and use that as a starting point for my space. I wanted to experiment with the way materials were used. If I think it’s okay, I’ll try to use this kind of connection in spatial design too. I’m curious about how different materials can be connected, and I even feel like it could be a metaphor for something bigger, but it could also be something I’m thinking about and sublimating.

Is there a theme you continuously explore in your work?

There have always been a few themes, and the keywords I mentioned above are one of them. They’re also what I’ve written in my profile. My profile is actually quite short, but I’ve always been intrigued about how materials connect to each other in a more limited way. Or that the spatial design is put under limited conditions. I’m not looking to explore a very universal design, it’s a design that meets the various factors and are under restricted conditions. It’s my solution to budget, construction time, client requirements etc.

Looking back at all your previous work, which is your favourite?

It’s hard to say. I guess it’s hard to answer for any designer. Every time a project finishes, I can always pick out things I wish I’d changed. I think designers are always looking forward to the next one.

Which direction would you like your work to grow and develop towards?

I still want to be able to give myself more freedom when I’m designing. I can feel that I’m influenced by certain things when I’m designing. Sometimes it comes from something I like and other times it comes from something I don’t like. Both of these restrict me. I want to be more free and not be influenced by these restrictions.

What do you think is the point of making art when the world undergoes extreme upheavals?

I can only speak about the impact on me. During the pandemic, I was surrounded by absurd and adverse news every day — it would make me stressed and my mind wouldn’t be able to calm down and concentrate. It’s not a comfortable state to be in. Therefore, I tried to do work everyday. I think making art and doing work is very similar. People need to be engaged in a laborious activity — one that immerses your body and mind in silence, in order to keep your mind at peace while working, and to not get distracted by bigger things in the world that we’re not in control of. After all, I still have to live. I still have to eat, sleep, and go to the toilet. Life goes on even if it’s shit out there. So I couldn’t let myself live in that state everyday. People need this kind of labour to “paralyse” themselves — to blindfold themselves and escape for a while.