Birthing Future Cities of China

During one my of my first classes at university one of my professors asked us: “What do you think about when you think of China?” His point was to lay bare our misconceptions and prejudices towards a country most of us had never visited before but were eager to learn about. But when, upon shooting down every single one of our answers, he said “People! Crowds and crowds of people!” he unwittingly revealed his own misapprehension. China’s population is reaching 1.4 billion but the country doesn’t lack space and, as its relatively low population density reflects, under-crowded areas do exist and are not too difficult to find – many of them are the suburbs enclosing high-density urban areas, others are simply rural regions and natural landscapes. Yet, it is difficult to imagine an underpopulated Chinese city where roads are not permanently debilitated by traffic jams and have enough space on the sidewalk for people to walk on without ceaselessly brushing each other’s shoulders. It is no surprise that in recent years many journalists and media outlets have relished the opportunity to reveal to the world the phenomena of Chinese ghost cities – new developments springing up in many parts of China that appear eerily and unreasonably uninhabited. “Welcome to the city of Ordos, a city of the future,” announced Melissa Chan in her 2009 report for Al Jazeera. “Brand new and built in just 5 years, and meant for 1 million residents. But no one’s moved in, the city stands empty.”

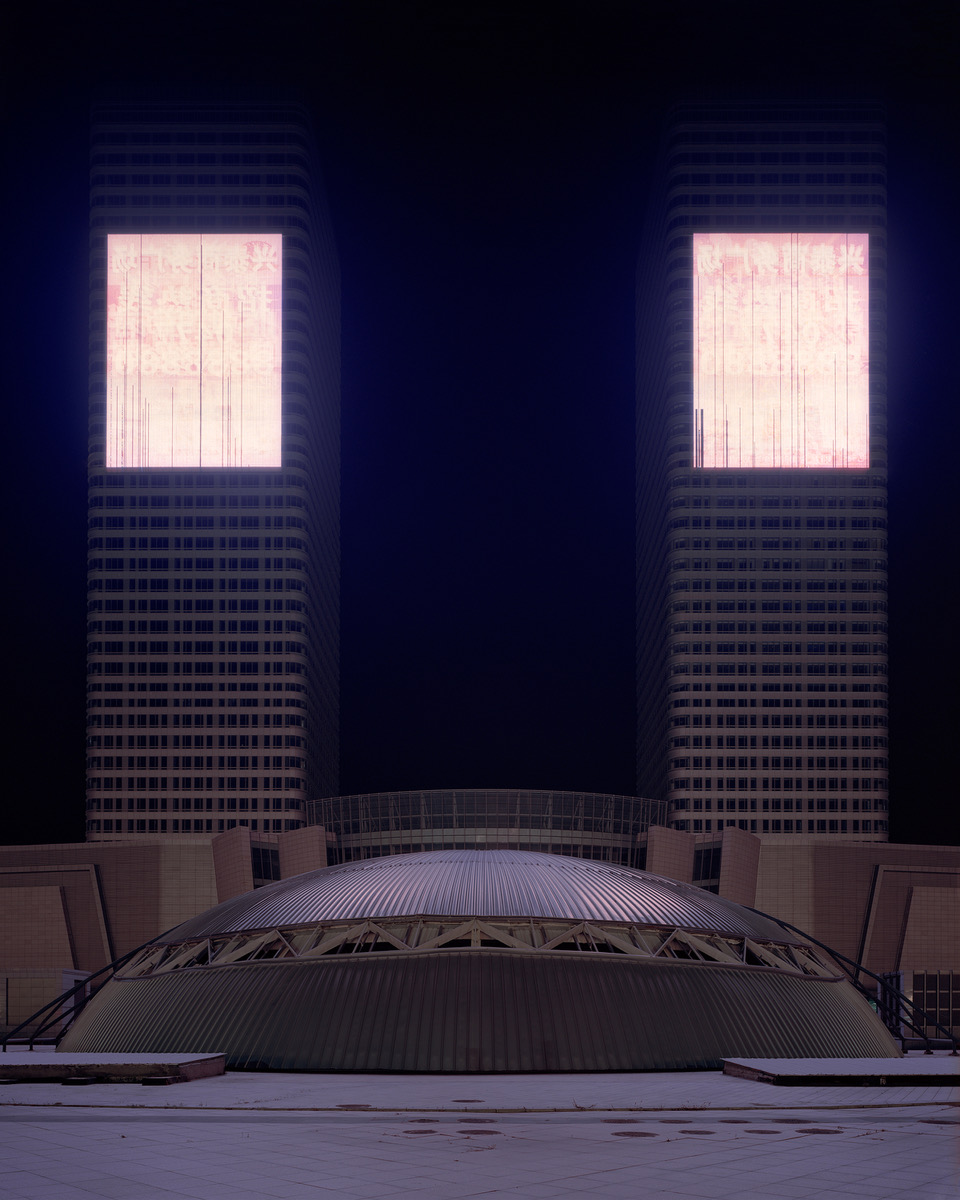

But is it really so? As an increasing number of articles have shown, all of these new developments are only relatively empty, in many cases because they haven’t been fully constructed yet, in others because they haven’t existed long enough to be inhabited. As journalist Wade Shepard puts it in his book Ghost Cities of China “[they] are a temporary phenomenon. It is just a phase that new cities move through between construction and vitalization.” Intrigued by the many sensational reports, Chicago-based photographer Kai Caemmerer set out for China to explore these new developments, consequently producing a collection of evocative images published under the title Unborn Cities. His conclusions echoed Wade’s. “The term ‘ghost city’ is a misleading and improper way to describe any of the new cities in China,” believes Caemmerer, “the term implies that the population has left or abandoned the areas, which is not the case. What I see are cities that are just beginning to wake up; cities that are taking their first breath.”

One of the many developments he visited was precisely Kangbashi. In 2003, the government started building this new district in the old city of Ordos in Inner Mongolia and, after thirteen years, Kangbashi is only just starting to develop its own life, steadily transitioning from an unborn city to a young city full of very real possibilities. “While it is far from being vibrant and busy, there is an overwhelming feeling that it won’t be long before it is,” explains the photographer, recalling his first impressions of the city’s urban landscape. “I wanted to focus on that feeling. Instead of showing buildings in the central square of Kangbashi as being lifeless and without light, as many images do, I chose to show them emanating light as if to suggest that they have, or soon will have, an audience.”

China has been building cities at an incredible rate, going from 69 in 1949 to the 658 of today. The government actively promotes urbanisation and it plans to move 300 million more people into cities by 2030. This process doesn’t simply consist of building new urban conglomerates from scratch on former rural land, but has also assumed many different and at times dystopic courses. A common phenomenon is the creation of a better, newer and possibly eco-friendly “twin city” within the original one, such as Meixi Lake Eco-City in Changsha. This futuristic project devised in 2009 was designed to complement the natural landscape, integrating buildings with parks, mountains and canals whilst providing its inhabitants with all the instruments to live in harmony with the surrounding environment. According to Wade, there are plans for 300 eco-cities to be built, but seeing as none of them have been completed as of yet, it is still unclear whether these new developments will actually be non-invasive for the environment – needless to say, many are sceptical. As Caemmerer points out, “The idea of a city is not the most eco-friendly of concepts, so the term ‘eco-city’ has always felt a bit oxymoronic to me. From an aesthetic standpoint, the Meixi Lake development does appear to have embraced an ecological design. The amount of green space and natural landscaping seems to outweigh what I saw in other new developments. In other words, it looks like an eco-city, but I don’t know enough about its design to know if it actually approaches low-carbon or ecological ideals.”

Meanwhile, China’s mega urbanisation plan also includes swallowing up entire villages in a process that has been called “chengzhenhua” or ‘townification’, where rural land is reclassified as urban. This process creates what architect Rem Koolhaas (speaking with Nathan Gardels of The WorldPost) has defined as “scapes”, whereby post-urban conditions enclose rural and urban landscapes. In his vision, China’s future landscape won’t be formed by the traditional succession of isolated rural and urban areas anymore, but will be a continuous amalgamation of the two, combined in a number of “mega-urban clusters.” These will provide “much more fluid movement between city and country, density and low density, north and south, east and west.”

Unsurprisingly, China is not only building new cities but is also actively creating new space for them: reclaiming land from the sea, filling rivers and moving mountains. A project of this scale and ambition seems to have been lifted directly out of a science-fiction novel, but in a country that has the potent combination of means and resources as China, it is completely feasible. According to Koolhaas, what makes it possible “is not so much authoritarianism as such, but [the country’s] ability to plan long-term and mobilize the political and economic resources to realize those plans,” combined with “an intelligent form of maintaining a bureaucracy that can shape things.” However, this might be a naïve point of view on a process that often involves the forced relocation and eviction of rural families from their homes and land – with or without an adequate compensation depending on the case. New areas are also often forcibly populated by relocating administrative buildings, public institutions and universities, leaving students and state workers little choice but to relocate as well.

Herding the rural population into an urban setting is not just a matter of offering them improved living environments and better benefits such as schools, healthcare and pensions– although these certainly help. There are consistent cultural differences in lifestyle between the two, and more often than not villagers may feel displaced in an urban environment, bringing a series of complications the government needs to deal with. Song Ting and Adam Hames Smith have captured Ordos Kangbashi’s local administration’s efforts towards integration in their documentary The Land of Many Palaces, filmed between 2012 and 2014 and following the relocation process. “Neighbours and friends,” announces a community supervisor, “we are trying to create a more civilized city, so how do you become a civilized person?” The farmers are taught how to use modern toilets, showers, stoves and televisions, while advised to be “civilized” with their mouth, hands and feet with a long list of do’s and don’ts. “Don’t shout loud. Don’t smoke in public areas. Don’t throw trash around. Don’t vandalize.”

China’s new urban landscapes as captured by Caemmerer, with their half-built districts and sparse population, might look dystopian and sometimes unnecessary at the moment, but they definitely shouldn’t be considered ghost cities – they are not dying, they are coming to life. “Many of these new cities are not expected to be complete or vibrant until 15-20 years after they begin construction,” explains the photographer. “They are built for the distant future, and at present, we can only speculate on what form they will take when they reach this point in time. Because of this, I find it appropriate, if not ideal, to make images that lack context and ask more questions than they provide answers to.”