Cyril Duval: Illuminating Darkness

Also known as Item Idem, Cyril Duval dissects consumerism through intermingling concepts in his work. The Parisian born, newly Los Angeles-based artist discusses his devotion to his audience, reflecting the times, and advertising pop culture’s socio-cultural grandeur.

Shanzhai refers to the Chinese appropriation of luxury and trademark labels in the form of knockoffs. Shanzhai Biennial is an art collective influenced by Shanzhai culture formed by yourself and your two partners, Avena Gallagher and Babak Radboy. How did you find yourself in the world of Shanzhai?

Personally, I’ve been working with those subjects for over ten years. I lived in Tokyo from 2003 to 2008 and I travelled around China while the idea of Shanzhai was still brewing and emerging. I work with a lot of readymade objects in my sculptures; I collect them like a sort of artist hoarder, accumulating references that deal with late capitalism and mistakes in products’ branding. Throughout my travels I kept in touch with those guys – my two partners – and after some time collecting those many objects, we thought we should start something with them.

The first idea was to create a curated store where we would present them, and then we actually decided to start a venture that would be more of a conceptual project. Basically, we were trying not to do Shanzhai but to be Shanzhai; to be a Shanzhai brand. Shanzhai started with electronic knockoffs in Shenzhen, but perhaps the most prominent knockoffs are fashion garments. But if you look into it in depth, Shanzhai exists on every level of production within the Chinese industry. It’s a spirit of creativity that we decided to embody, but the whole point was not to be a mechanism within the system, it was to be on top of the food chain – becoming an entity that is purely Shanzhai in itself.

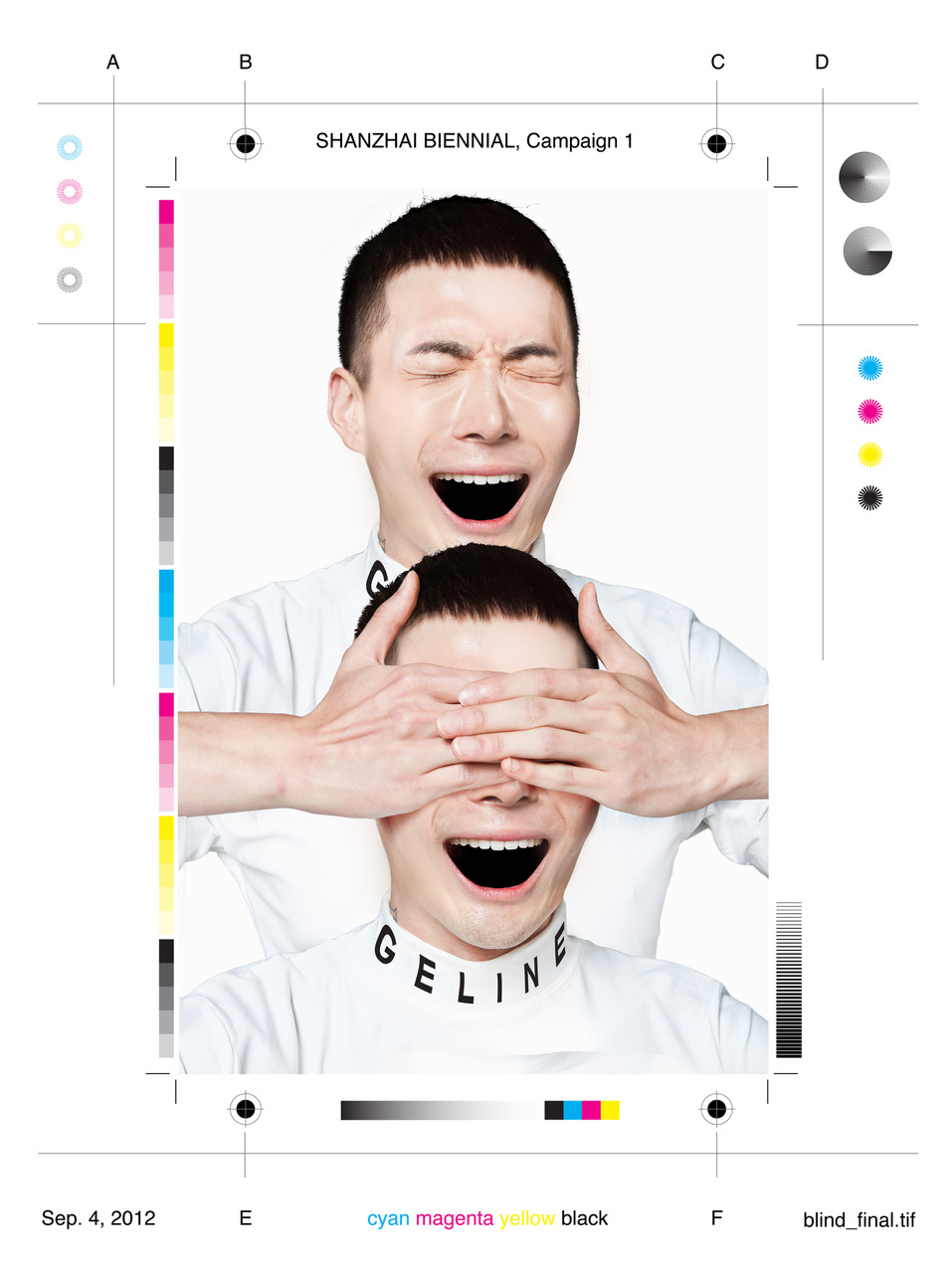

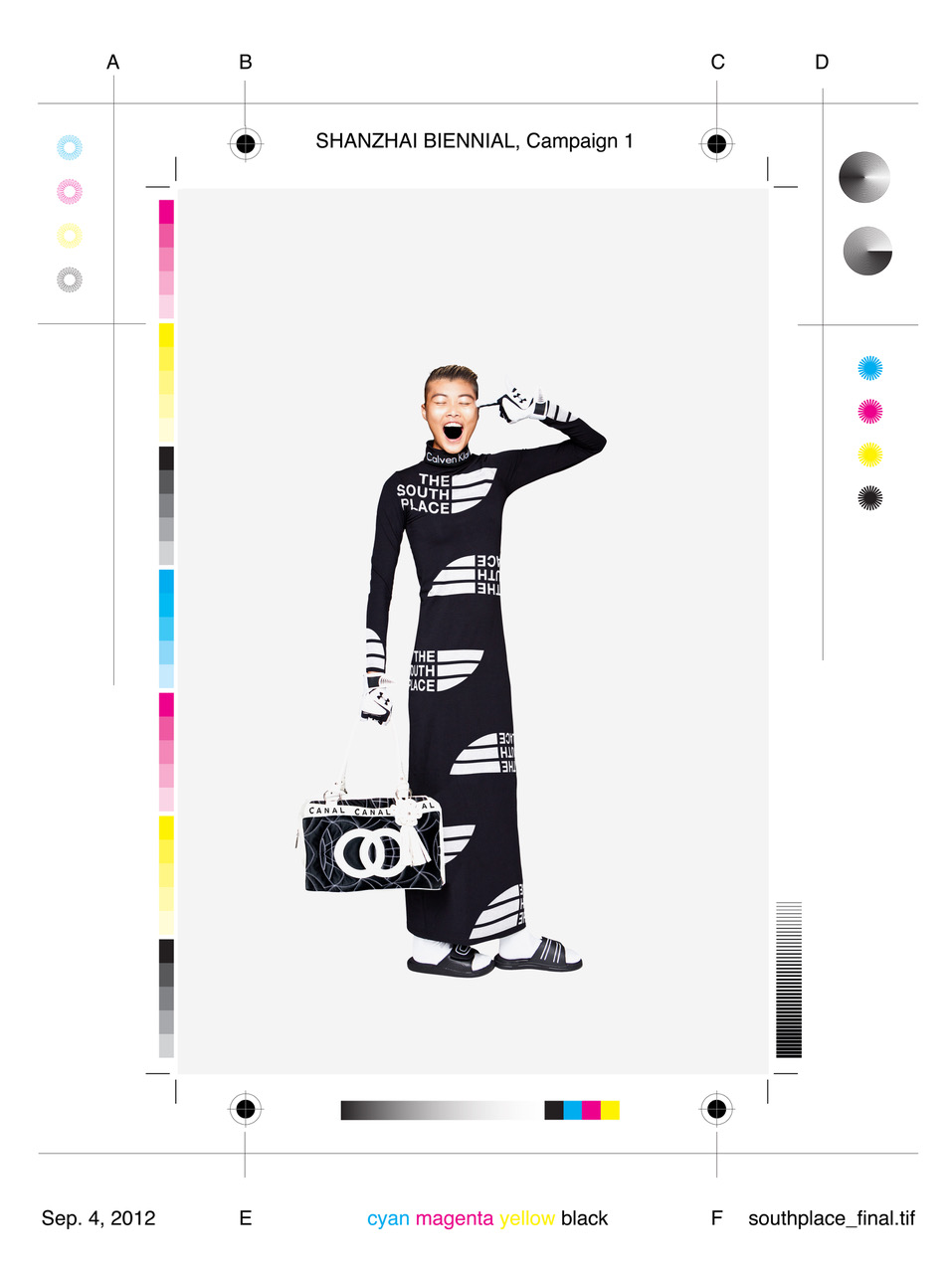

Each of our incarnations is like a global artwork. A mixed-medium design piece for which we create a branding strategy, a graphic identity, a fashion and image campaign, and products—either physical or not. For the first biennial we created virtual products and advertisements made only to promote the brand. People would contact us asking where they could find our products, but they never actually existed physically.

It seems like one of your most dedicated goals is to transform. With Shanzhai Biennial you’ve transformed advertisements by way of what you call “commercial abstraction”—not to be misunderstood with corporate aesthetics. Can you elaborate?

The imagery needs to be able to lean into certain subtleties in terms of creating images that have an aesthetic. For example, the fashion vocabulary is very easy to use, but it must be tweaked to explore different ideas. The first Shanzhai Biennial campaign was inspired by Chinese artist Yue Minjun. He paints those exaggerated, laughing faces in repetitive patterns and sells them for millions of dollars, but he’s also the most counterfeited painter in China. We were sort of hinting at this language.

The second biennial was more of a take on Shanzhai as a critical comedy. We created a beautiful dress embroidered with sequins that looks like a Head & Shoulders shampoo bottle, and then made a video campaign for it using the song Nothing Compares 2 U by Prince and Sinead O’Connor. The funny thing about it was that we wanted to use a version in Chinese but couldn’t find one. Suddenly, on a completely random website we found a drag queen singing the song in Chinese, so our Chinese assistant wrote down the words and we had our model lip-sync them as we filmed her on a platform. Then, we sent that to a Chinese singer who sort of made her own lyrics out of it. So in the end there were like five levels of appropriation. It plays with the peculiar as well as the familiar.

It’s such an interesting song choice as well, especially when you’re focused on recognisable branding. You’re saying that ”nothing compares” to the real product.

Yes, it’s sort of a love song between the consumer and the product, as well as admiration for the product itself and for Shanzhai itself. We did a small mockumentary during a show at MoMA PS1 where we actually pretended to be curators from a city called Shanzhai. Many people actually think Shanzhai is a city, so we thought, “Okay, let’s make it a geotag.” We pretended that the model was a conceptual artist working in the field of appropriation in music, and that she was touring in China with Daft Punk. We sort of created this storytelling of myths and rumors, being very Shanzhai.

There is also the intention to create a very complex brand identity and really flesh out the maintenance of a brand from a business perspective, right? You blur the lines between art and advertising.

Absolutely, we’ve always been very careful about what we are doing. There’s a lot of research behind our work, we’re not simply a streetwear label that puts two logos together. Our approach is more conceptual, we work with a lot of consideration which is why we work mostly with commissions—we’re like artists for hire if I may say (laughs). Our first biennial was commissioned by Beijing Design Week, and we released its Yue Minjun inspired campaign in Modern Weekly, which is the most important fashion newspaper in China and distributed to almost a million copies a week. The plan from the beginning was to stay true to ourselves and to advertise ourselves as a brand. Even the term brand, or collective, doesn’t exactly fit with our practice… our concept is more fluid.

Separate from Shanzhai Biennial exists another brand name, Item Idem. Explain to me this self-appointed moniker, which I’ve learned is a Latin term meaning “the same”?

That is correct. It was an instinctive decision I made when I was still very young and finishing art school. Item Idem is a way to brand myself and create an artistic entity, a label that could encompass all of my practice. I’ve been involved in design, architecture, creative direction, fashion styling, sculpture, installations, performances… quite a lot. There is always an attempt at levelling these concepts and disciplines: art and fashion, or art and design; mass market and luxury, or conceptual art and visual communication. Item Idem is a balance of these things, so my practice is very, very broad in that sense.

There’s a sort of ambiguous attitude in which you can never pinpoint exactly what category I fit into. Ghost rituals and the consumption of paper objects in China for funerals are an extension of what I’ve done with Shanzhai because they’re fake logos that deal with intellectual property, product image, brand image and so on. What is most interesting is that they tackle this weird conundrum between consumerism and spirituality. How is that possible to exist within the same vessel, within the same object? I’ve done massive research in China to try and understand. I do less art and fashion and design now; my practice has evolved into something else but it’s still very much Item Idem.

Is your ambiguity intentional? Do you embrace a sense of mystery in never landing on one concept or another, and constantly evolving instead?

Like everyone else, I deal with structural parameters – the question of “What do you do and how do you make a living out of it?” Those sometimes influence your practice, but for me as an artist it’s very important to never be pigeonholed into something in which you lose track of the essence of your creativity. It’s important to respect yourself as an artist and to try to evolve. I’m always tempted to learn new techniques, to work with new collaborators, to do things that are… not against people’s expectations, but just simply not expected. My next big project is a documentary film, so it’s very different from the glamorous, quirky, eye-candy filled vocabulary that I would normally use. How it will be perceived is what interests me. It’s not the most accessible practice, but I feel comfortable with that because it gets deeper into something that’s actually more interesting and more…

More informative.

More informative and less gratuitous. I mean, I’m in my late thirties, I have more important work to do than just make cool, fun images.

So essentially, you’re ready to get to the point.

Absolutely. My work is becoming a little more serious, I would say. The new project that I’m doing is an extension of all my research on Chinese paper objects that once again deal with the means of production of what China has, because those traditional crafts are now becoming mass-produced and the objects have evolved. Those that are burned for funerals, like a Louis Vuitton handbag, deal with mass consumerism themselves. Their aesthetic is sort of post Shanzhai. It’s very interesting for me to see an image of the ghost product that encompasses the shape and the value—the emotional value—of the real, but is fake at the same time, or more of a shell of the image of a product. I started making sculptures out of them, turning them into vaguely Damien Hirst-esque pieces floating in silicone on LED pedestals. They were mass consumerist objects but bigger, almost as religious altars.

Tell me more about your upcoming documentary film. I’m curious about how you approach filmmaking and what initially drew you to work in that medium. Personally, I would be most gratified to wield and experiment with the extension of auditory elements available with film.

The new film is called Tales of Fortune, which I’m releasing next year. The name is very Item Idem in its duality – fortune is wealth, but it’s also destiny, consumerism and spirituality. I toured Asia with just a little steadicam, my iPhone, and a GoPro and interviewed artists that have knowledge about that: ghostbusters, feng shui analysts, UNESCO historians, traditional paper makers, retailers, all kinds of people. It does take the shape of a documentary but it will develop into a strange visual art piece. I’m translating everything in Mandarin and English because I want it to function as a communicational vessel between both cultures, I don’t want it to be a westerner talking about China to a western audience.

I’ve been experimenting more and more, but at first I was really scared to actually film myself and to deal with the technical aspects. I worked with mostly one person, Cheng Ran, who is a contemporary artist and filmmaker. Together we made the film JOSS in which Chinese papier-mâché objects burned in slow motion set to religious music. That was the beginning of these new bodies of work that I have. JOSS was a complete collaboration, but since then I’ve decided to go solo with new projects.

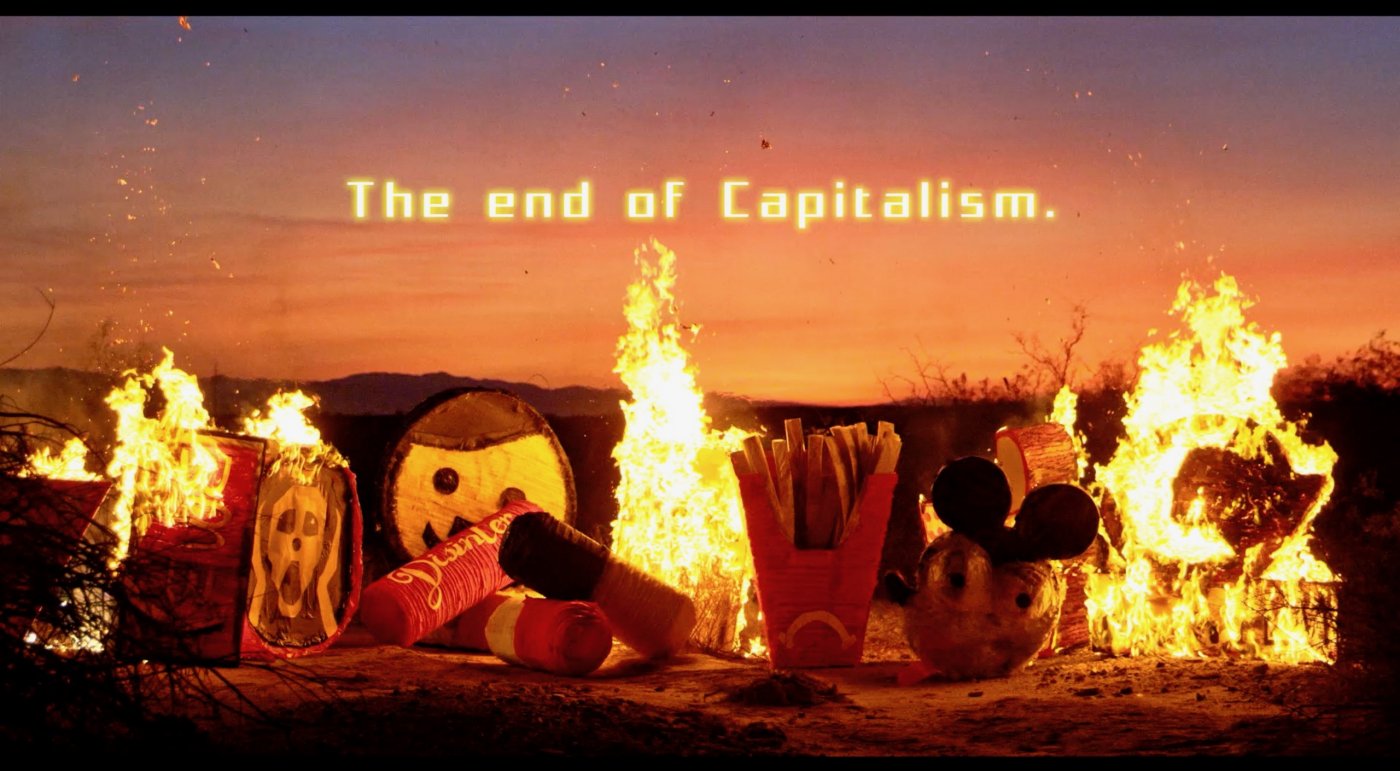

The films that I did last year were anticipating the rise of Trump in a very nihilist point of view, filled with melancholia and a little queer. For the film NUII, I had beautiful models in the California desert destroying twenty piñatas that I designed. The piñatas referenced images of consumerism and mass marketing like Monsanto and religious consumerist ideologies: the KKK, Trump, Scientology, etc. that link to the vessel of what money encompasses. Each piñata was red and white, which are known as the power colours used in extreme branding like Coca Cola, the Nazis, or totalitarian imagery. To that I added yellow, so there were important colour codes. It’s a 35-minute film with Trump on fire, so it’s extremely violent and extremely sad, but there are still pop undertones even when it’s really dark. I actually released it on the day of Trump’s inauguration.

In transforming dark themes of momentous world issues into something resembling pop art—equally striking yet physical, playful and subtly whimsical—is accessibility on your mind? It seems they are intentionally masqueraded as something more palatable.

Absolutely. I strive to reach the audience through a range of emotions, so yes, it’s always something that is kept in mind. Playfulness and humour are qualities that I find very important. When I look at art myself I want to fall in love with it; I want to be entertained or I want to be disturbed. A good work of art needs to have some of those qualities; it can be extremely light or extremely dark, but it needs to provoke something. The art market needs to exist but I rarely make anything with commercial art in mind, and maybe I should do it a bit more but it’s truly about the audience.

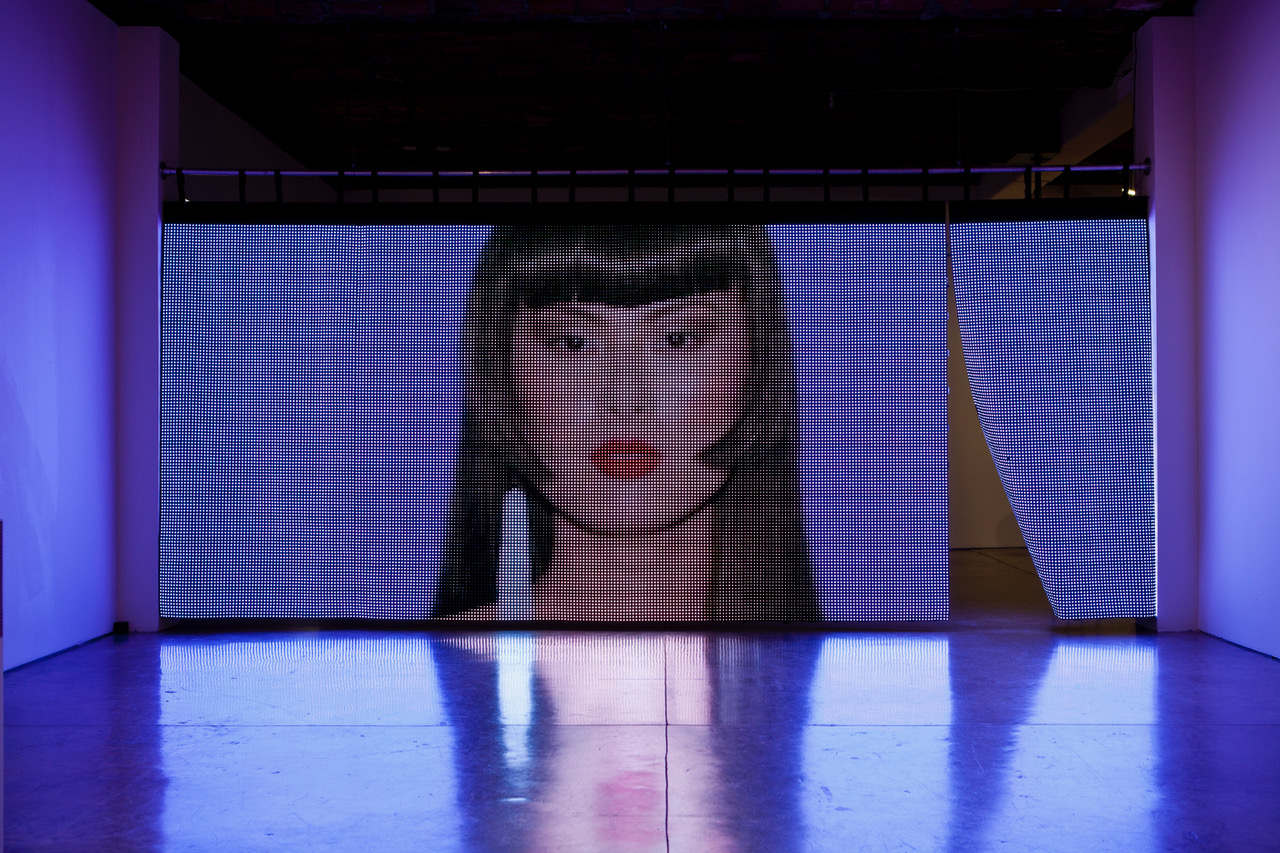

JOSS was done four years ago and it’s still touring in museums. It was in Sydney for four months at the White Rabbit collection, which is one of the largest collections of Chinese contemporary art. They showed the film as part of a gorgeous video installation and they sent me a note saying that people were in absolute awe looking at the film. The audience was silent, or if they needed to speak they would whisper, and some people were brought to tears. Literally, that email was the best email I’ve ever received in my life. And I wept for days because I thought it was the nicest thing… it’s the nicest reward for the work I put out there, to know that I can affect the viewer in ways that sort of transform them, even if just for a minute. This is really what is at stake here, I feel like artists need to have a position within the world where we’re commentating but not really fully criticizing. We need to be playful and somewhat detached from the political or hyper-political.

That reminds me of a quote by Nina Simone as she spoke on an artist’s duty. She felt that every kind of artist has a responsibility to “reflect the times.”

I love her. There are great artists dealing with politics and creating amazing works through performance or radical gestures. I’m not saying we should all do that, in fact I think it’s great that a lot of people are not doing it. I do it at times but I don’t want to be categorised as simply someone who focuses on those topics. I do love to tackle problematics, but in a way that opens doors rather than being staged at one single angle, because otherwise it’s just visual propaganda. Finding ways to create a conversation, a reflection, or self-critical thinking and leave the audience with a huge laugh or a couple of tears is the goal. The conversation depends on the type of work, and I think it’s relative to the notion of sublime. Works of art that are created to deal with the absolute and spiritual are made to give that feeling of awe and adoration. I’m not trying to trick people into falling in love with my work, but I’m interested in communicating something extremely beautiful that brings forth very strong emotions. JOSS is the one that succeeds the most in that regard.

The new documentary won’t have the usual eye candy, its focus is to share culture and information which is extremely important to me. The age we live in is crazy—with fake news, what does information even mean anymore? I try to give emotion and to give meaning. I’m less into provocation. I don’t mind making provocative art because it generates discussion, but I don’t do shock value, it’s the most basic trick to use. It’s interesting to make things look beautiful but it fails if it’s beautiful and dull.

You’re using pop imagery as a guise of something the majority of people could be intrigued by and willing to conceive, or at least contemplate, more readily and openly. Maybe that’s also a way to make the work itself more enjoyable for you when you have these threatening topics at the forefront of your mind, so let me ask: are you enjoying it?

NUII was so sinister. I mean, it’s beautiful, but maybe I need to take a step back a little bit from that. There’s momentum. We live in a very dark time and I think it’s important to embrace that—I don’t want to only see art that’s fun and smiley and not reflecting reality. But again, it’s about finding the right balance in how you play with those codes and how you express them visually. Conceptual art is rarely the most accessible medium but if you can blend it with pop culture or other things like fashion, why not? It’s tricky, some projects are more successful in that way than others. Also, I’m a very emotional and well-informed person; I read more news than I look at fashion. I’m very aware and that’s my way of being active as an individual. I’m not a militant who will go out into the street to fight against the cops, but I do believe that I can try though my art to be part of the conversation. To answer your question, I don’t know if I enjoy it… I’m a very playful and light person, but at the same time I’m a realist about the shit show we’re living in. It’s good to be honest about your emotions.

I want to ask you about one of your recent exhibitions, “Method of Loci,” which is defined as a means to enhance one’s memory by employing knowledge of personal environment, or spatial memories, to recall desired information. Can you tell me more about it?

It emerged very naturally. I was focused on this ability that my brain has, that every brain has, to connect many different things at once. I thought, “How am I able and why am I able?” It’s about creating a visual map of my brain in its current state through my works. I build a spiderweb of references using logos, products, film, and new materials that I create myself that become separate little storytelling vignettes. One of them is about the rise of nationalism in Europe and in the world; one is about the Nazi movement in Greece or the rise of the alt-right globally; another talks about recession in the eurozone. They have pop art qualities but open a dialogue about something much more realistic and troubling.

I try to use all the resources I have, either physical or conceptual to create connections between what I find to be relevant. I do spend a lot of time analyzing the things that I buy and I wonder what they mean and what it means when I put them in relation with something else. I’m very interested in this creation of narratives by simply pairing two readymades together.

And devising a method of addressing your viewer in a way that will trigger their own personal memories with recognisable imagery.

Exactly, and at the same time there was an honest, metaphysical approach to what it means to be a human being and an artist in the time we live in. Two years prior the project, I was in a nearly fatal accident, so my work has been gaining emotional depth. I’m researching spirituality for the new film because that’s what it will be – spirituality versus the physical existence embodied by the consumer.

“Method of Loci” was the foundation but I didn’t apply the actual method, I used it as a metaphor to express my whole being and my many references. In the flyer for the exhibition, I used the Neuschwanstein Castle in Germany which was commissioned by Ludwig II and inspired Walt Disney in designing Cinderella’s castle. There’s certainly a relation with branding and popular aesthetic. I also asked geopolitical and ecological questions—I had a praying mantis and huge, inflatable roaches repainted with hard rubber material – a metaphor and dichotomy between humans as slaves and humans as predators.

For this issue, we apply ‘fake’ as an umbrella term encompassing ideas of imitation, transformation, illusion, etc. which coincide with Item Idem and prevail in the heart of Shanzhai culture. What are your thoughts on fake as a concept?

The original definition of Shanzhai is mountain refuge, dating back to medieval times in China when warlords would take fine goods from the cities. It’s the Robin Hood mentality in which you steal capital and you redistribute it. Shanzhai is a creative process that hacks into capitalism and fucks with intellectual property to create new content. I always emphasize that counterfeit is the emulation of the real —a fake Louis Vuitton bag is made to look real, so it perpetuates the status quo of classes and people who want to appear rich. Shanzhai is the opposite—it’s not trying to look real as a fake, it is real because it blends several symbols at once to create new intellectual material. Many people understand that, many do not. In China where those goods are produced, people have amazing fashion and swag in the streets and the subway. Then you have the grassroots of society that work in factories willing to make their own goods, and then the middle class who is interested only in luxury goods and the real real. I think many people are embarrassed about this sort of cliché that China is the creator of fake. I see it as the pop art of China, it’s an intellectual, anti-capitalist approach that shatters everything else and creates something new.

Finally, I wanted to ask you about your recent move to Los Angeles. What brought you there, and how might the city influence your future work?

I really needed a change of scenery. I had lived in Japan for five years and then in New York. New York is an amazing place, but it sort of sucks the life out of you from within. New generations come constantly and the city goes through phases of being extremely creative and then less creative and very gentrified and commodified. California is one of the most beautiful places in the world in terms of nature. The light inspires me so much in relation to many important visual artists that worked here in the sixties with the Light and Space Movement. I’ve grown more fascinated by nature whereas before I was more of a city boy. In terms of landscape, I’ve lived in very busy, compact, vertical cities and now living in a horizontal city feels completely different. I think of Los Angeles as the furthest point of the Western world, it’s very isolated. The artistic community is small but vibrant; people are ambitious but not like in New York where everyone is desperately trying to get their piece of the cake, and I like that difference. It’s more relaxed, and I’m at a point in my life and my career where I no longer feel the need to be at the center of everything. In Los Angeles I have new things to study: the modernist aesthetic, Hollywood, the obsession with the purity of the body and plastic surgery… it’s fascinating. I don’t necessarily focus on those subjects, but I’m curious about them.

It is interesting—obviously Los Angeles has a reputation of being artificial, not always in a pejorative context but in terms of veiling the truth, sometimes in a tongue-in-cheek way. Considering that, it feels like a place where your specific style of art can really thrive. It’s also fitting with your venture into filmmaking. You’ve got a lot of resources at your fingertips.

Exactly. I wouldn’t be surprised if my work becomes more and more influenced by the environment, but so far NUII is the only piece that I’ve done that deals with Californian aesthetics and culture. I feel that every artist coming to California for the first time should make a road movie, and that’s what I did with NUII. It’s very dystopian and resembles the Mad Max films. The longer I stay here, I’m sure I’ll be drawn to Hollywood; I’d be delighted in time to move in the direction of visual effects and makeup prosthetics or work with production studios. I approach it as an amateur, but there’s a lot to be done here. Time will tell.