Looking for the Motherland – Kurt Tong explores memories and identity between Hong Kong and China

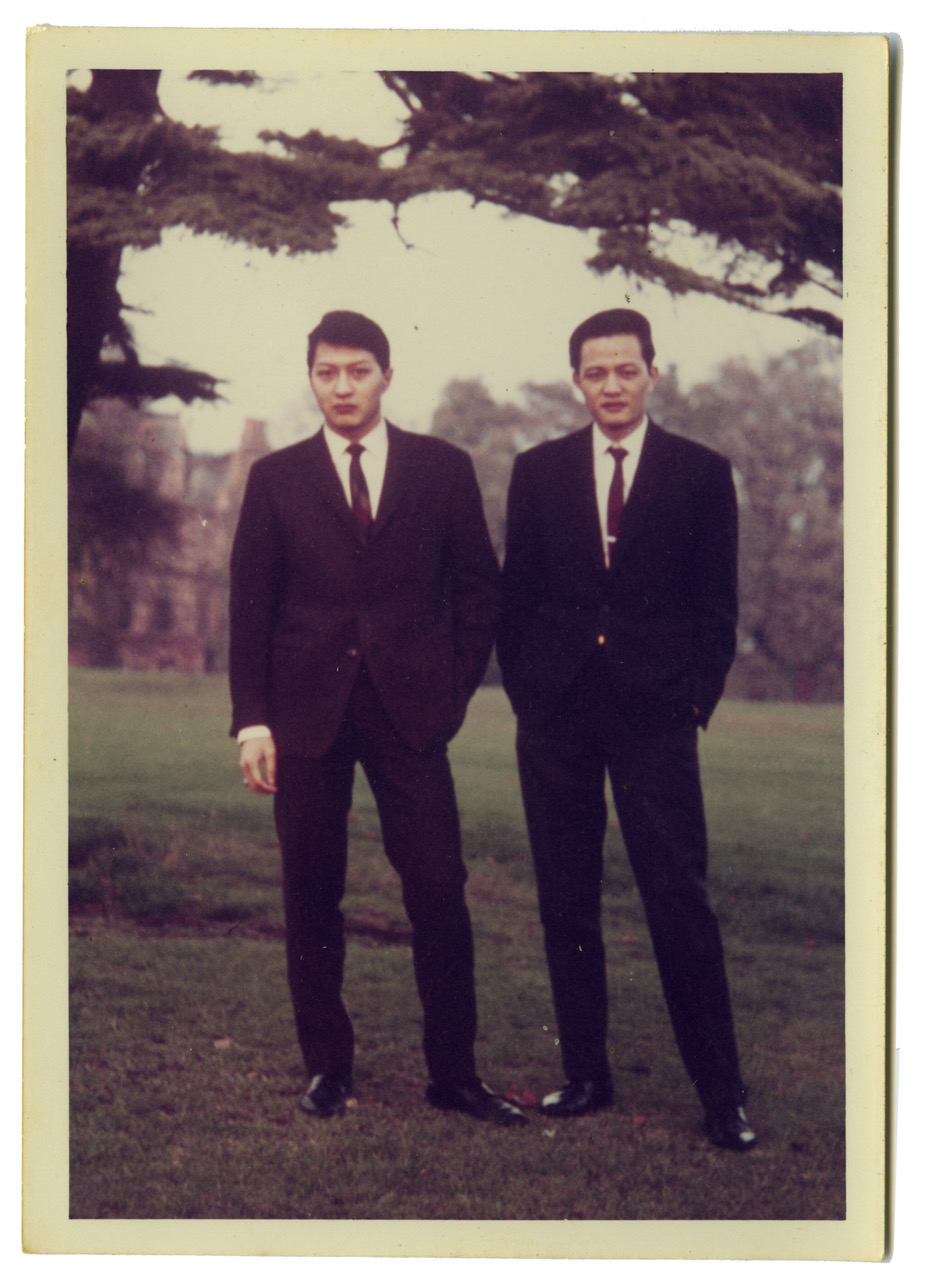

Kurt Tong has a simple and straightforward way to explain the very personal emotions and life experiences that trigger all of his current photographic work, his voice getting more and more enthusiastic as we talk on the phone. It’s a rare sunny afternoon in London, but in Hong Kong it’s already past 10pm and Tong has just put his kids to bed. Late Skype calls are not unusual for him, he explains, as his network of promotion and support is still very international, made of frequent trips to Europe and even more frequent weirdly-timed interviews. This is not only because the Hong Kong art scene can be at times frustrating, but rather because the photographer has spent most of his life in different places. Born and raised in Hong Kong in the late 1970s, he moved to the United Kingdom at the age of thirteen to join his brother in boarding school, then university brought him to travel around Europe, the Americas and Asia, with a particularly long stop in India working for an NGO. It was a time dedicated to exploring new things and places, focusing on what was outside himself and capturing it on camera. “It was during that time that I started taking photographs,” explains Tong. “I really got into it and did a long term project that actually got me a prize in Spain which opened a few doors. At the time I thought, ‘this could be an amazing career path!’ Fourteen years later—it was a big mistake!”

Photography clearly wasn’t a mistake, he only needed to slightly adjust his direction. So in 2006 Tong went back to London for a Masters in Documentary Photography, which helped him discover his true calling. “I went to it thinking, ‘that’s what I want to do’ but by the time I graduated I didn’t want to do photojournalism at all,” he says. “Before then, I was travelling a lot and I always thought that I was getting in depth into different stories, but during my MA I realised that I was never really scratching beneath the surface. Ever since then, all my projects have been based on looking at myself and my surroundings, exploring what I already know rather than travelling to far off countries to learn just the basics.”

With this new aim ahead of himself, Tong has started an inward journey that has brought him to face with the complicated questions of identity, memory and belonging, connecting them to an exploration of his family history divided between Mainland China and Hong Kong. Some of his findings have been beautifully summed up in The Queen, The Chairman and I, a photographic project that combines new photographs with found family portraits and writing, underlined by a pressing question: how Chinese am I or indeed, who am I?

Ahead of his new exhibition at Lumenvisum, Hong Kong, opening on October 14 we talk to the photographer about his personal quest for a homeland.

In an interview with Jonathan Blaustein on aPhotoEditor back in 2012 you said: “throughout my twenties, I saw myself as a citizen of the world. I spent a lot of time in India, and Eastern Europe. So I thought wherever I was, I was home. It wasn’t until my daughter was born that I started feeling Chinese again.” Do you think that this change is something that comes naturally with growing up and being a bit less naive in the world?

I can’t speak for everyone, but with me it was definitely when my daughter came along. She is mixed race—my wife is from Scotland—so suddenly I felt this urge to teach her about being Chinese, especially because we were still living in London at the time. It came from that, me wanting to have a better understanding of being Chinese so I could teach her.

You grew up between two cultures as well. Did you feel like you had to have a sort of self-discovery before you could teach your daughter?

When I had her—we’re going back ten years now—I didn’t speak very good Chinese and I hadn’t lived in Hong Kong for about 20 years, so I really didn’t have a good grasp of what being from Hong Kong meant, what being Chinese meant. I was very much in need to discover that, so I started to find out more. The more I found out the more I wanted to make work about it.

How was moving back to Hong Kong after being in the UK for so long?

Really hard. We came in 2010, when I started the project The Queen, The Chairman and I—that was the whole me reconnecting with Hong Kong. The first time I came, because I knew we weren’t staying permanently, it was quite easy. I was learning about being in Hong Kong, living here, but I didn’t have to make friends. I didn’t have to grow my roots again. When we came back in 2012 we bought cats, so that was permanent. And yes, it was hard. I suddenly realised I had to make friends, I had to live here full-time. It was a real culture shock, being fully back in a culture I grew up in and trying to fit in again.

Your first projects, such as People’s Park and Memories, Dreams; Interrupted explore our relationship with memory, our interpretation of the past, and especially how our brain alters memories. How did you become fascinated with these themes?

Part of it is that I love old family photographs—the aesthetic of it and the styling. But what I also love is that when I ask my relatives to describe these photographs, every time they change [version] and everyone comes up with a different story. That is the starting point of all my projects really: how people attach memories to old photographs and how they reinterpret [them], every time differently.

Since you are very interested in family photographs, are you keeping your current family album?

Yes. Not artistically, but I take a lot of photographs and I do print them and I make albums every year. In a very traditional sense.

That’s what my family does. We have this huge archive with pictures of everyone that go back to my grandparents’ childhood. It’s amazing. It’s so important to have such a record of years that you don’t remember and things you don’t remember you have done, because when you see the pictures things come up. As you said, sometimes it’s not exactly what happened, but you can reconstruct the past.

When I did the family book project I’ve learned that only the really bad memories or the really good memories stay, all the middle-ground ones get lost. So people are always like ‘oh he did something evil’ or ‘he did something really good.’ It’s never like, ‘he was ok.’

How do you relate to this tampering process?

I can speak in relation to specific projects. With Memories, Dreams; Interrupted it was a real physical exercise. I started photographing my daughters’ parks in a very straightforward way, but the images weren’t working at all. Then I read about how memories are constructed and how the brain breaks them down into small pieces on a science journal. We only store the 40% of them all, of these building blocks. Every time we bring up a memory, the brain fills in the other 60%. I wanted to replicate that process, so I literally destroyed the negatives and tried to salvage only some information from them. With the following one, The Queen, The Chairman and I, people always say ‘it’s great that you have this archive of family history!’ But I always tell them, first of all half the stories are not real. It took me eight months to collect all these photographs and stories before I even began to take my own pictures, and for every story there were four different versions. So it’s very much my own version of a story. When I show the work, it’s never about the book itself. I set up a Chinese tea house within the gallery space where people coming to see the show can look at the photographs and sit down. There is always someone serving tea, so they are drinking tea and they are reading my book. What I’ve found is that by Chapter Three they stop reading the book and start talking about their own ancestors. It works every time! When I first did the book I was worried that it was too Hong Kong-centric because it’s all about the Chinese diaspora. But it worked across all cultures. I remember the first opening night, a Portuguese guy came up to me and he said ‘I love this book, it’s my story!’ I was a bit confused. Then he told me how his parents were born in Mozambique and then when the colonies ended they both had to move back to Portugal. I realised that the whole 20th century, the last 150 years, are all about immigration and people moving across borders. The real project is actually the conversation that happens within the tea house. For me that’s the artwork, my book is just a catalyst. Going back to your question, I guess my job is to prompt people to think about and dig deep and find out their own memories and their own histories.

Sweet Water, Bitter Earth, your latest project, is a research for a connection with your lost homeland, China, through travelling and photography. You said you felt an emotional connection with the landscapes. What do you mean?

The whole four projects preceding it were about me reconnecting with my being Chinese, whilst the starting point of Sweet Water, Bitter Earth was that I wanted to find out whether I could connect with China as a country and as a land. I started photographing my two granddads’ hometowns, both in South China. One was a family of fishermen, while the others were big landlords. I took loads of photographs scoring my old ancestors’ homes, but I couldn’t make any connection; they weren’t interesting. I realised that the reason why I couldn’t connect was because they both left [China] over a 100 years ago. One left over a 120 years ago to see if there was a better job, and the other left in 1949, because he was a landlord. I then asked myself, ‘if I can’t find my China in these two places, what do I look for when I go to China?’ So I started researching my own visual language of the country and I realised all my preconceived visions. As a kid I never went to China, I was 27 the first time I went. All of my teenage and preteen images of the country came from this one documentary, which was made by the Japanese about the Silk Road [The Silk Road by NHK]. I grew up with this really romantic idea of what China looks like, mainly images in a very foggy, expanding landscape. When I went there and I went all over the place, every time I saw one of those empty landscapes with very little people, that’s when I connected with China, because that’s what I though China was.

That’s what you recognised, the memories of what you saw before going there.

Yes, that’s what I thought China was, a very expansive, very foggy, very sandy landscape.

At the same time you felt alienated by people.

Yes. Going to China is a real culture shock. When I first came to Hong Kong and I started going to China I knocked a lot of my preconceived ideas. Growing up in Hong Kong in the 1970s and 1980s, we felt more superior to people from the Mainland, but when I started making friends in South China all those barriers went down. I connected with people from the South. But every time I travel up North, I again get a really fresh culture shock.

Yes, there is a massive difference between the South and the North, like visiting two different countries.

Yes, so you know what I’m talking about. My Mandarin is not the best, I mean I’ve been learning it since I came to Hong Kong and I can converse in South China. The Southern accent I can deal with, but as soon as I go up north I can’t understand a word people are saying. It’s kind of refreshing my culture shock in different parts of China. In the project [Sweet Water, Bitter Earth] as you go through the sequence, from the beginning to the end, the figures in the images get bigger and bigger. Every time I actually got close to them I felt more alienated, because suddenly they wanted to speak to me and then as soon as I opened my mouth they realised I was not from there. The way the work is laid out shows that the closer I got, the more you see human figures, the more disengaged they are, with me and with each other. They are always on their phones and not looking at each other.

You also acted physically on the negatives of Sweet Water, Bitter Earth, placing them under your shoes or immerging them in sea water. How did you come up with the idea?

Ever since Memories, Dreams; Interrupted I have been doing things to my negatives. I think it’s just what I enjoy. I always find just taking images quite restricting and I’ve always been fairly tactile and physical with my prints and my photographs, so it was almost a natural pattern that I would do that.

Are you working on new projects for which you will do both?

Yes, my work now focuses on trying to mix media. At the moment I’m actually pearling some rice for my next project on Self Combed Women (自梳女), a tribe of women who used to work in the silk industry. Women’s status in China has always been pretty bad, but they were in this area where there was a lot of silk trade and women made a lot more money than in the other parts of the country, so they were more independent. When the silk trade started going down towards the end of the 1800s, they couldn’t make money anymore but they were used to that lifestyle where they didn’t have to listen to men. So when it was time for them to get married, they basically would take a chastity vow and they would comb-up their hair in a certain way and dress in a certain way. Once they did that they could leave their hometown and they could go out and make money. If you go to Singapore or Malaysia you’ll find a lot of old photographs of them in a pigtail, white tunic and black trousers. When they took their vows they weren’t allowed to go home so many of them, when they retired, put together the money to build houses. There are a lot of spinster’s houses dotted around South China, where they would go and retire. I’ve been working on a project on them for a long time and then I realised it was too general and too broad, so now I’m focusing on just one person and her life story.

What are you using the rice for?

She was an unwanted daughter and she wasn’t allowed to go to school, she was abused. Throughout her whole upbringing she wasn’t welcomed, but during the famine in the 1950s, when she was working in Hong Kong, her whole family was starving to death and she would go home every month and bring food for them. That’s what kept them alive, so I’m making a lot of rice sculptures. I really connected with this project again. Sweet Water, Bitter Earth is about misconnection and the lack of a connection, and that extends to how precious I am about that work. I don’t love that project, but that’s kind of the whole point of it. Whereas this project, I’ve started it three months ago and it’s developed really well. I’m really excited about it.

You started your series The Queen, The Chairman and I with a question: How Chinese am I or indeed, who am I? Did you find your answer?

It was really clear. People from Hong Kong never say they are Chinese, they always say I’m from Hong Kong. In my 20s I travelled around the world and I never felt Chinese, but after the project I’m very proud of being Chinese. I think people in Hong Kong see being Chinese in relation with China in the very modern, Communist sense. But now I realised I’m proud to be Chinese because of its 6000 years of culture and history as opposed to what’s happened in the last 50 years.